News

The Institute’s latest eLearning course – “Reaching Across Cultures” – equips learners with essential skills to navigate cultural nuances when it comes to organ and tissue donation among diverse populations. The content was developed in partnership with Dr. Heather Marie Gardiner, professor of social and behavioral sciences at Temple University’s College of Public Health. Gardiner recently joined Instructional Designer Shimrit Lee to discuss her research and the importance of education in fostering a more inclusive and effective donor community.

Shimrit Lee: Tell us about your research.

Heather Marie Gardiner: My work focuses on addressing health disparities, particularly in the realm of organ and tissue donation and transplantation. At the Health Disparities Research Lab, my team and I are dedicated to improving the organ donation process, reducing transplant inequities, and increasing access to transplantation services for marginalized communities.

SL: What kind of methods do you use to track disparities?

HMG: I employ a mixed-methods approach, drawing on both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. This includes developing and implementing protocols for in-depth interviews and focus groups and employing structured and semi-structured surveys. Additionally, I apply advanced statistical methods to analyze data and uncover patterns and disparities in health outcomes related to organ donation and transplantation.

One of the core aspects of my research is community engagement. At the Lab, we actively involve underserved minority populations in our research initiatives to ensure that our work directly addresses their needs and challenges. This community-centered approach not only informs our research design and implementation but also enhances the impact and relevance of our findings.

SL: What do you see as the most significant barrier to transplantation for marginalized communities?

HMG: First, I just want to emphasize that no population is a monolith. Plus, it’s nearly impossible to identify a single barrier to donation. Among African Americans, for example, disparities in donation are rooted in a complex interplay of historical mistrust of the medical system, concerns about fairness in organ allocation, and cultural and religious beliefs.

To overcome these barriers, targeted efforts are required to address misconceptions, improve education about the organ donation process, and rebuild trust within the healthcare system. Community engagement, culturally sensitive outreach, and collaboration with religious leaders can play pivotal roles in fostering a greater understanding and acceptance of organ donation among this group. Efforts must focus on promoting transparency, equity, and inclusivity within the donation system to encourage broader participation and ultimately save more lives.

SL: What is the role of education in reducing these barriers?

HMG: Training in culturally humility is integral to ensuring organ donation professionals understand diverse perspectives and engage in respectful and effective communication. This involves dispelling myths, addressing concerns related to religious or cultural beliefs, and being aware of how implicit biases may affect interactions with patients and families. Training in trauma-informed approaches is also key to understanding the emotional and psychological aspects of donation conversations. These are all topics covered in the eLearning course that the Institute is offering.

Education efforts should align with policy changes aimed at reducing disparities in donation opportunities. This includes advocating for equitable access to donation services and addressing systemic barriers that disproportionately affect certain communities.

Lara Moretti has been providing bereavement counseling and support for families of organ and tissue donors since 2003 at Gift of Life Donor Program (GLDP). Currently the Director of Family Support Services at GLDP, Lara has served as secretary and co-chair of the AOPO Donor Family Services Council. She is also a member of the Gift of Life Institute’s faculty, where she leads trainings on the impact of loss and grief on family donation conversations. Lara was recently a named a Fellow in Thanatology: Death, Dying and Bereavement from the Association for Death Education and Counseling for demonstrating knowledge, experience, and education in death, dying, and bereavement.

We sat down with her to learn more about thanatology and its application to her work at Gift of Life.

What is thanatology?

Thanatology is the study of death, dying, and bereavement and the impact death has on those who are grieving.

What prompted you to study it?

As a bereavement counselor for donor families, I wanted to increase my knowledge about grief so I could better support the families we serve.

What have you learned about grief through your fellowship that surprised you?

I have been surprised by how resilient families are. Even though they have experienced a major loss, they show grace and compassion and can grow from the trauma they endured. Also, I have a greater appreciation for grief after non-death losses, such as the loss of one’s health, job, or home.

You work in family support services. How has your study of thanatology impacted your work in supporting donor families and recipients as well as the information you share through the Institute?

I feel I have a more well-rounded understanding of grief and that has allowed me to support families and recipients in their different displays of grief. Helping grieving individuals understand that what they are experiencing is normal can hopefully alleviate some of the pressure they put on themselves to grieve in the “right way.” There is no one right way. There is only your way.

In my work with the Institute, I see how critical it is to train donation professionals about acute grief so they can be better prepared to support families in conversations about donation. Most health care professionals have no formal training on grief so we enter the field with our own perceptions and ideas about what grief should look like.

What do you wish more people understood about grief?

In general, I think we are a fairly grief illiterate society even though all of us will experience grief in our lives. I wished more people understood that grief can manifest itself in not just emotional reactions but also spiritual, physiological, and cognitive reactions as well. Additionally, grief is not something that needs to be fixed or cured. It is a long process that must be experienced after a loss.

The field of organ and tissue donation is one of high stakes. In other industries, performance improvement might equate with more units manufactured and sold, more money made, or stock price increases. In ours, it means more human lives saved.

Providing effective feedback to OPO employees on job skills is a critical route to performance improvement. Giving feedback constructively can drive organizational performance in the grand scheme by affecting employee performance at the individual level.

Coaching

Employee skills coaching can take many forms. What is possible through coaching depends on many factors, such as the coach-trainee relationship. For instance, what is possible within an established manager-employee scenario may not be feasible within an online skills coaching scenario and vice versa.  In Gift of Life Institute’s WebEncounter training platform (an online application in which participants can role-play according to specific scenarios), the trainer has the advantage of a sometimes healthy separation that is unaffected by “office politics” or the reticence that can accompany mock role-play work and critique between established colleagues. However, this scenario is constrained by limitations in depth of knowledge about the learner’s background, career goals and so forth. The manager and employee scenario has the advantage of breadth of knowledge and observational time with the trainee, yet may be constrained by other factors such as routines, schedules, and ingrained ways of relating in an established relationship. Regardless of limitations and advantages imposed by the specifics of the relationship, giving feedback effectively is an invaluable business asset.

In Gift of Life Institute’s WebEncounter training platform (an online application in which participants can role-play according to specific scenarios), the trainer has the advantage of a sometimes healthy separation that is unaffected by “office politics” or the reticence that can accompany mock role-play work and critique between established colleagues. However, this scenario is constrained by limitations in depth of knowledge about the learner’s background, career goals and so forth. The manager and employee scenario has the advantage of breadth of knowledge and observational time with the trainee, yet may be constrained by other factors such as routines, schedules, and ingrained ways of relating in an established relationship. Regardless of limitations and advantages imposed by the specifics of the relationship, giving feedback effectively is an invaluable business asset.

Feedback

Despite its potential, the word “feedback” can send shivers up an employee’s spine which, in turn, may limit the coach’s inclination or ability to effectively use this critical tool. Furthermore, organizational culture often dictates feedback philosophy. For instance, if feedback is seen being delivered up and down the OPO hierarchy as a means of overall organizational improvement, it is more readily accepted than if it’s being used as a non-productive critical element (i.e., a weapon).

Despite its potential, the word “feedback” can send shivers up an employee’s spine which, in turn, may limit the coach’s inclination or ability to effectively use this critical tool. Furthermore, organizational culture often dictates feedback philosophy. For instance, if feedback is seen being delivered up and down the OPO hierarchy as a means of overall organizational improvement, it is more readily accepted than if it’s being used as a non-productive critical element (i.e., a weapon).

The Ken Blanchard Companies report that the three primary reasons people resist giving feedback are:

- They’re fearful the other person will get angry;

- They’ve tried before and didn’t get results;

- They’re not sure how to do it effectively.

Fortunately, giving feedback effectively is a skill that can be learned:

- It is important to approach an employee feedback situation from a basis of respect.

- Do your pre-work. Gain as much insight into the employee as possible (e.g., background, professional strengths and opportunities, passions). The extent to which this is possible varies considerably based on the type of coaching situation, but is often possible to some extent with just a bit of effort and time.

- Convey your own belief about how opportunities for growth translate into improved job performance and outcomes. Strive to attach the potential growth experience to something meaningful for the specific employee and overall OPO performance.

Managers sometimes fail to see learning and career development as an important aspect of their roles which, in turn, can limit their drive to master the delivery of effective feedback. But what can come from good feedback is actually pretty exciting. Current weaknesses or gaps ARE near-future opportunities! This means more lives can be saved, more families can feel their loved one live on, and more people can leave an extended legacy. It’s important for each manager to channel their inner coach and know that growth in an area that is personally meaningful to the employee can also be an incredibly rewarding professional experience.

Know Your Environment

The organ and tissue donation work environment is unique. It is often filled with long hours and colored by heightened emotions and the knowledge of how important outcomes are to the lives of so many. Providing feedback and coaching in these circumstances requires special attention to timing, delivery, and the employee’s state of mind. Being mindful of states of physical or emotional exhaustion is important so that timing of communication can be adjusted accordingly for both employee compassion and feedback efficacy. It’s also important to regularly recognize that most professionals in the OPO field are passionate about their work and serious about their performance. Knowing that this means that staff may be their own greatest critics can remind those providing feedback to approach the employee with respect and the feedback as a valuable, important opportunity.

The “A-ha Moment”

When coaching an OPO professional on a job skill or mindset, strive for that meaningful moment when everything comes together and creates a lasting change for the employee. Executive coach Kathleen Martin advises on getting an employee to that “A-ha moment”:

When coaching an OPO professional on a job skill or mindset, strive for that meaningful moment when everything comes together and creates a lasting change for the employee. Executive coach Kathleen Martin advises on getting an employee to that “A-ha moment”:

- Resist the urge to push but, rather, recognize how important timing is to the learning of a new skill or perception.

- Utilize pauses and silences rather than fight to avoid them. Yet know when to nudge. By paying close attention to the employee you may notice when they are holding back but are ready to move with some assistance.

- Notice energy level changes. There can be a discernible shift after an “A-ha moment” that paves the way to move on.

- Celebrate success. This can be as simple as allowing a few moments to allow the shift in realization to sink in.

- Solidify the learning by establishing an action plan. Summarize the learning that has occurred, establish a plan for the employee to put the skills into action, and set a realistic plan for follow-up.

Effective employee skills feedback can have profound effects. All staff in the potential role of “coach” to donation professionals should embrace this opportunity for powerful individual employee and organizational growth.

References:

http://www.kenblanchard.com/Leading-Research/Research/Take-the-Fear-Out-of-Feedback

https://leaderchat.org/2016/03/22/5-tips-for-coaching-to-the-aha-moment/

Elizabeth Spencer has been working in the OPO community since 2002. She was with Washington Regional Transplant Community (WRTC) for nine years, serving as both Director of Hospital Services & Professional Education, and in the clinical division as a Senior Clinical Recovery Coordinator. As Director of Hospital Services & Professional Education, Elizabeth was responsible for oversight of partnerships with area hospitals regarding the implementation of donation best practices, donation educational programs for various hospital staff, hospital data analysis and reporting, hospital donation strategic planning, and hospital policies related to organ and tissue donation.

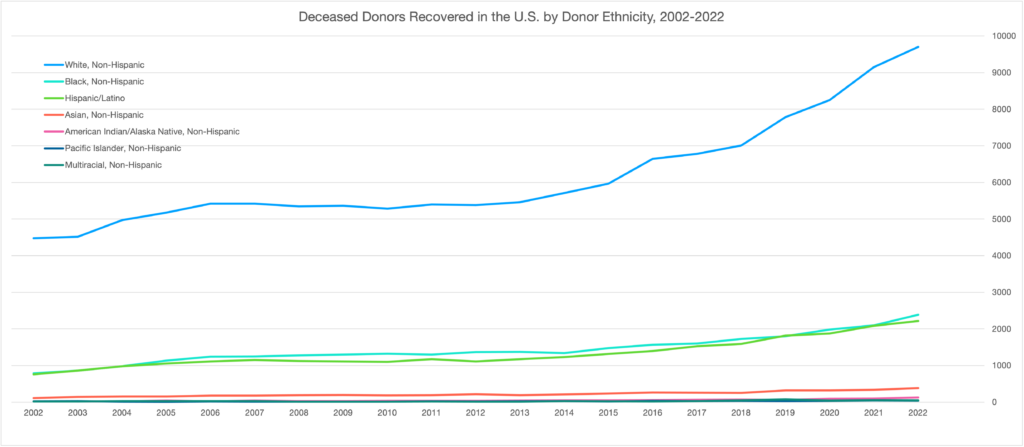

Drug and opioid overdose deaths are on the rise across the country, increasing by approximately 140% since 2000. Significantly contributing to this increase is the usage of natural and semisynthetic opioid pain relievers, heroin, and non-methadone synthetic opioids. 2013 to 2014 saw increases of overdose deaths related to those specified opioids as 9%, 26%, and 80%, respectively. Recommendations to reverse this upward trend of opioid related deaths are: improving safer prescribing methods of prescription opioids; expanding access to and use of antidotes (such as naloxone) and increasing access to medication-assisted treatment combined with behavioral therapies; and collaboration amongst public health agencies, ME/Coroners, and law enforcement agencies to improve detection and responses to identified drug overdose outbreaks.

While public health agencies struggle to identify measures to curb this rapidly increasing and often fatal trend, donation professionals find themselves more and more frequently faced with overdose victims who have become potential organ donors. Families of these victims are emotionally depleted by often years long battles to help their loved ones overcome their addiction, only to find that the battle has culminated in their worst nightmare. All has been lost. There will be no more trips to rehab or late night calls for help. The more we can gain insight into what families have experienced, the better able we become to offer the resources and support each unique family may need. Consider having a parent or spouse of someone who has suffered from drug addiction and died, come in and speak with your staff. Their stories are powerful, and the opportunity for staff to ask questions and learn more about what considerations they should keep in mind when caring for these families are significant. When talking with health care providers who feel drug addiction and overdoses render individuals incapable of offering the gift of life through donation, be sure staff have solid talking points that can help them convey the positive outcomes that can be achieved through donation. Start a conversation among your own staff to be sure everyone has the information they need to communicate effectively in these situations with families and care providers. If you are doing something at your OPO related to the increase in potential donors regarding opioid overdose that could help other professional be more effective in this area, please share; we’d love to have you participate in our blog.

For more information on this growing epidemic, click here.

Patricia Mulvania has more than 30 years’ experience in the healthcare field, beginning her career by providing emergency patient care in the pre-hospital setting. Since, Patricia has served in leadership roles in the emergency department, home-care, and hospice arenas.

The Transplant Games of America are elusive to most yet significant to many: a week-long extravaganza that closely mirrors the world’s beloved Olympic Games. And, like the Olympics, opening ceremonies provide an emotional recognition of the unity and shared experience of everyone present. Intense competition transpires on the courts, fields, pools, and halls as participants strive to bring home the most medals. The stands are completely occupied by exuberant fans decked out in their team’s gear. Workshops, coffee houses, quilt displays and vendors offer a break among the rivalry.

Yet, these games differ quite drastically from the Olympics in several substantial ways. The participants are not world class athletes, but individuals who have been given a second chance of life through transplantation. The passionate crowds in the stands are not your typical spectators either; they are donor families honoring their loved ones’ memory, living donors, Transplant Centers, Organ Procurement Organizations, and all the incredible people who comprise the support system of the transplantation community.

The competition is an obvious testament to the success of transplantation. It is quite striking to step back and consider that the athletes once connected to the more than 100,000 on the waiting list are now able to shoot hoops, swim laps, and swing a racket because of the compassion of another. Although recipients summon their athletic prowess partially to bring home the gold, their primary intent is to demonstrate their appreciation for this second chance and to honor their heroic donors.

Donor Families & Recipients

The Transplant Games provide a different experience for donor families. Observing healthy recipients exuding zeal for life allows for the presence of positive feelings around the tragedy of their loved ones’ death. Donor families are invited to participate in many special events, including a tribute ceremony and a butterfly release. Numerous workshops are offered with topics pertinent to loss and bereavement. Families have the opportunity to create and pin a quilt square in honor of their loved one. The atmosphere at the Games is supportive and safe; a space where donor families may openly express their grief and share their stories. The life and legacy of the donor is omnipresent.

The unique beauty of the Games lies within the interactions between the donor families and recipients. Although the media often normalizes and sensationalizes meetings between the two parties, it is actually quite an uncommon occurrence. Many donor families never meet or even receive correspondence from their loved one’s recipients and vice-versa. However, at the Transplant Games, each recipient identifies every donor family as their own. Countless hugs and thank you(s) are exchanged throughout the week. Medals earned rarely remain long on the necks of the athlete as they are soon gifted to the closest donor family member. The boundaries of team loyalty do not exist here, the appreciation and awe is palpable from all.

A Personal Observation

Accompanying Team Philadelphia for five days in San Diego, CA for the Games was an unforgettable and profound experience. Our team wonderfully represented the Transplant Foundation in our vibrant uniforms and proudly celebrated our donors. Together we conquered the games and proved that transplantation works. We hope that our efforts in San Diego will demonstrate the importance of organ and tissue donation and that we adequately honored our donors and their families who altruistically gave the gift of life.

For additional information about the Transplant Games, visit: http://www.transplantgamesofamerica.org/

Name, is a Title at Gift of Life Donor Program in Philadelphia, PA

Earlier this year I had the opportunity to present at the 2014 Transplant Donation Global Leadership Symposium (GLS) on “21st Century Learning: Building a Learning-Oriented Culture in Transplant Donation.” I joined two colleagues including Gloria Páez of Transplant Procurement Management (TPM) who presented on new trends in the teaching role and technology applications and Maria Stadtler of Methodica, LLC (formerly of OneLegacy) who presented on customized training. My presentation was about eLearning and the principles that make it an excellent option for educating the donation professional.

Earlier this year I had the opportunity to present at the 2014 Transplant Donation Global Leadership Symposium (GLS) on “21st Century Learning: Building a Learning-Oriented Culture in Transplant Donation.” I joined two colleagues including Gloria Páez of Transplant Procurement Management (TPM) who presented on new trends in the teaching role and technology applications and Maria Stadtler of Methodica, LLC (formerly of OneLegacy) who presented on customized training. My presentation was about eLearning and the principles that make it an excellent option for educating the donation professional.

Dr. Ruth Clark, noted instructional psychologist, defines eLearning as “content and instructional methods delivered on a computer and designed to build knowledge and skills related to individuals or organization goals.” This simple definition defines:

The what: training delivered in digital format;

The how: content and instructional methods to help learners master the content, and:

The why: to improve performance by building job-relevant knowledge and skills.

Add to this definition three key elements that distinguish eLearning from other learning platforms: instructional methods, instructional media, and media elements.

Example from a Gift of Life Institute elearning module

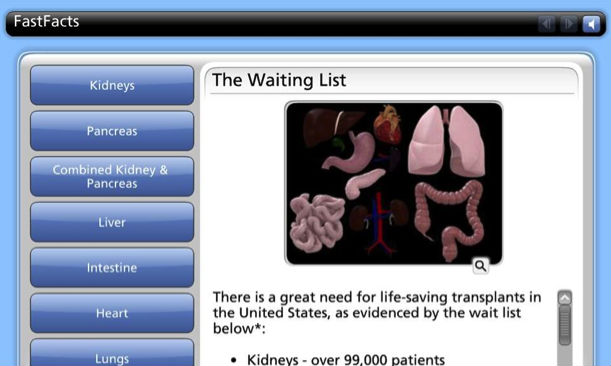

I imagine some of you are asking: Instructional methods? Instructional media? Media elements? What does all this mean? These are the basic concepts you should consider when developing an eLearning module for your audience. Instructional methods, (e.g., practice exercises, simulations and analogies), are the techniques used to help the learner process new information. Instructional media are the delivery agents that contain the content, including workbooks, computers and instructors. And, finally, media elements refer to the graphics, text, audio and video used to present content and instructional methods. For example, in the screen at left, media elements include text, graphics and audio narration tied to specific organs.

While doing additional research, I came upon the work of Dr. Richard E. Mayer, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His research interests are in educational and cognitive psychology, and for the past 10 years, he and his team have been conducting controlled experiments on how best to use audio, text and graphics to optimize learning.

Dr. Mayer’s work concludes that six media elements are critical to successful learning.

- Multimedia: adding graphics to work improves learning. Use illustrations, line drawings, photographs, animation or video. It’s important to make sure the multimedia elements are consistent with the instructional message. For example, if you want to provide a visual on the number of people waiting in the United States for an organ transplant (124,000+), you might use a photo of a packed house at Michigan Stadium (seating capacity of 110,000).

- Contiguity: when graphics and text are aligned on the screen, the learner doesn’t have to work as hard to retain the material.

- Modality: explaining graphics with audio improves learning.

- Redundancy: research shows that learning is greater when graphics are explained by audio alone, rather than audio and text.

- Coherence: remember, less is more. Using gratuitous visuals and sounds can hurt learning.

- Personalization: use a conversational tone along with first and second person improves learning.

The 24 eLearning modules the Institute had developed thus far incorporated five of the elements Dr. Mayer identified. We do not fully embrace the personalization by using first or second person as independent research indicates that our learners prefer the use of somewhat more formal language. You would need to decide for your organization and learners if personalizing the modules in this manner is appropriate.

Whether you are developing the eLearning internally at your organization or looking to an outside source to assist you, I recommend you become familiar with the work of Dr. Mayer and his colleagues to help you in securing eLearning that will result in effective learning for your donation professionals.

Theresa A. Daly is Director of Gift of Life Institute in Philadelphia, PA