Grief & Bereavement

At times of tragedy, parents and many professionals feel a strong impulse to protect children from what is happening. Usually, families are thinking about this decision for the first time, so it is valuable to share some of the following information about children’s grief. However, it is important not to expose children to experiences that they may be too young to understand and these recommendations will not apply to most children under the age of four years.

- Children are typically very clear about their preferences; when they wish to say goodbye, with appropriate support, it is a constructive experience. Equally, a child who expresses reluctance should not be pressured.

- Being left out can leave children with a lifetime of regret and recriminations, especially if the child has expressed a wish to be present.

- Children’s fantasies about what they are not permitted to see are often much more gruesome and frightening than the reality.

- Preparation allows the child to voice questions and fears and have them answered.

SUGGESTIONS FOR PREPARING A CHILD TO SAY GOODBYE

STEP ONE

Share information with the parents about the benefits of inclusion for children and describe the recommendations for preparing children. Offer your assistance but remember it is the parent’s decision to make. If parents do not wish to include their child, respectfully ask if there is any other way you can help.

STEP TWO

If parents accept your assistance:

- Sit with the child and his/her parent(s) and explain the option to say goodbye in age-appropriate language. Assure the child that the doctors and nurses have done everything they can, but haven’t been able to make their loved one better.

- Talk about the grown-ups being sad and upset… ask if that is hard.

- Ask the child whether s/he would like to say goodbye; say that you and their parent(s) will be with them and that they can leave as soon as they would like to.

- Use the “Some children…” technique to ascertain how they are feeling. (“Some children worry that it would be scary… what do you think?”)

- If the child chooses to say goodbye, use age appropriate language and describe the room, equipment, smells, noises, and (most important) what their loved one will look like.

- Check back with the child: “Now I have told you all about it, would you still like to say goodbye?”

- Some children change their minds at this point. If this happens, reassure them that it is good that they are making their own decision and offer the options of drawing a picture or sending a message to their loved one.

STEP THREE

When children say “yes”:

- Together with the parent(s) accompany the child into the room. It is important not to displace the parent(s) at this sensitive time. Additionally, it can be very helpful to parent(s) to hear how you talk with their child about painful topics.

- Point out to the child the things that you described (see STEP TWO, FIFTH BULLET). Go through all the senses (what do they see? hear? smell? etc.). Ask what else they are noticing and whether they have questions.

- Encourage them to talk to their loved one, to touch him or her as appropriate, and say goodbye.

- Again ask if there are any more questions.

Essential final steps:

- Sit down with child and parent and ask whether you did a good enough job of explaining everything. Did you leave anything out? Was anything worse than expected?

- RESTORE THE LIVING MEMORY: Ask the child to tell you about a time they had fun with their loved one. Ask about ordinary details (but try to go through all the senses to reinforce the memory): What did they do? What did they eat? What was the weather like? What did it sound like? Smell like? Look like? (all the colors) Did they laugh a lot together? Say how wonderful it sounds and that you understand how much they will miss their loved one “but you will always keep them and these memories in your heart.”

- To reinforce this message with younger children, make gathering motions with your hands (as though capturing memories) and pretend to put them in your heart.

- Check with the parent(s) whether they have questions and ensure that they are comfortable with what has happened.

Most children welcome the opportunity to say goodbye to a loved one and, when thoughtfully planned and carried out, this can be a strengthening and healing experience. Just remember, that although we have learned from research and experience that most children benefit from inclusion, it is important to acknowledge that the loss of a loved one is outside a child’s normal range of experience.

Cherry Wise began working in the OPO field in 1997 when she had a private practice as a psychologist and was a professor at the Wright Institute of Professional Psychology in Berkeley. Previously she was director of a non-profit organization that provided services to children and their families in times of bereavement or impending loss.

Typical concepts of death and grief responses for the major developmental stages of children are outlined below. It is important to note that there may be overlap between the age groups.

Infancy to Age 2

Concept of Death: This age group typically does not understand the meaning of death, but infants have awareness of loss and separation. They react more to the emotional reactions of adults in their environment and to any disruptions in their schedule.

Grief Response: Babies may search for the deceased and become anxious as a result of the separation. Common reactions include: protest, a change in sleep habits, decreased activity and weight loss.

Preschool (Age 2-4)

Concept of Death: For this age group, death is seen as temporary and reversible. Preschoolers usually do not visualize death as separate from life and don’t see death as something that happens to them. Typical comments include: “When will my mommy be home?” “How does (the deceased) eat or breathe?”

Grief Response: Typically this group’s emotional response is brief but intense, as they tend to be present-oriented. Preschoolers are more concerned about altered patterns of care or about the emotional reactions of adults in their lives. Other typical responses include: confusion, night-time agitation, frightening dreams and regressive behaviors, such as bedwetting.

Early Childhood (Age 4-7)

Concept of Death: This group still views death as reversible. Children sometimes feel responsible for the death because of thoughts or feelings that they’ve had about the deceased, sometimes called “magical thinking.” “It’s my fault. I was mad at her, and I wished she’d die.”

Grief Response: Repetitive questioning about the death process is typical of this age group. “How?” “Why?” They may play act the death or the funeral as an attempt to work through their grief. They may behave as if nothing happened. Other typical responses include: anger, sadness, confusion, difficulty eating, sleeping or regressive behaviors, such as bedwetting.

Middle Years (Age 7-11)

Concept of Death: This age group may want to see death as reversible but they begin to see it as something final. They still don’t think of death as something that can happen to them or their family members, but instead to old people or very sick people. They may believe that they can escape from death through their own efforts. They also might view death as a punishment (particularly before age nine). Children in this age group may develop fears of bodily harm and mutilation, and may fear that other loved ones will die.

Grief Response: This age group typically wants to know very specific details about the death. They may become concerned with how others are responding to the death. They may act out their anger and sadness and may have trouble progressing in school. They also may have a jocular attitude about the death, or may withdraw and hide their feelings. Children at this age sometimes become overly concerned about their own health. Other typical responses include: shock, denial, sadness and regression.

Cherry Wise began working in the OPO field in 1997 when she had a private practice as a psychologist and was a professor at the Wright Institute of Professional Psychology in Berkeley. Previously she was director of a non-profit organization that provided services to children and their families in times of bereavement or impending loss.

Early on in my role at my OPO, I listened to a colleague talk about a family he had worked with following the death of their young son. The father and the boy were in a car accident together. The father had some injuries but would survive. Sadly, his son would not so we were there to discuss with him and his wife, the boy’s mother, the opportunity of donation. This family went on to authorize donation and their son was an organ donor. My colleague, in reviewing this case, spent a significant amount of time talking about how “wildly emotional” the father was. The father was crying a lot and was often inconsolable. The child’s mother, on the other hand, was “stoic and cold.” The coordinator never saw her cry and he expressed concern for both of the parents’ emotional states I was new at my job so I didn’t feel as though I had earned the right to question this coordinator’s take on the parents’ grief. I did, however, wonder if the roles were reversed, if the father was the quiet one and the mother was the crying one, would my colleague have mentioned it all? Instead of being “wildly emotional,” the crying mother might have just been a “devastated mother” and the father would not have been “cold and stoic” but “strong and holding it together.” I’ll never know since I didn’t speak up but I wish that I had.

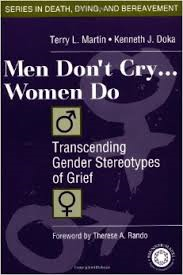

In 1999, Terry Martin and Kenneth Doka published Men Don’t Cry, Women Do: Transcendin g Gender Stereotypes of Grief. Their book emphasized that there are many ways people grieve but that there is a continuum of grief with two different patterns on either end. The Intuitive pattern, often stereotyped as female, is an emotional and affective expression of grief. The Instrumental pattern, often stereotyped as male, is where grief is expressed in a physical or cognitive manner. They assert, and I have seen in my practice, that there are both men who are intuitive grievers and there are women who are instrumental grievers and plenty of men and women in between.

g Gender Stereotypes of Grief. Their book emphasized that there are many ways people grieve but that there is a continuum of grief with two different patterns on either end. The Intuitive pattern, often stereotyped as female, is an emotional and affective expression of grief. The Instrumental pattern, often stereotyped as male, is where grief is expressed in a physical or cognitive manner. They assert, and I have seen in my practice, that there are both men who are intuitive grievers and there are women who are instrumental grievers and plenty of men and women in between.

When we approach families about donation, rarely are we approaching just one person. Even when there is only one legal next of kin, there are often other family members who are part of the conversation. Recognizing that grief can be expressed in a wide variety of ways can make us better at providing the right kind of grief support while discussing donation. Gender may impact the way someone grieves but it is not the determining factor.

The Intuitive Griever

This is the family member who is showing outward signs of their grief. They are openly emotional and that is how they process their grief. Do not try to stunt that emotion or re-direct it. You have to let the emotions flow. So these family members might be the ones with whom you just sit silently with a box of tissues nearby. You listen to them talk about their loved one. You encourage them to tell stories and share meaningful memories about their loved one. This will help them begin to process their loss and can also contribute to creating a trusting relationship with the procurement coordinator. Be wary of our healthcare partners defining these grievers as “over emotional” or “stuck.”

The Instrumental Griever

This family member is the one who is going to ask you a lot of questions. They are going to want to know all the details: When is the recovery going to take place? How will you identify the recipients? What kinds of tests do you need to do? With these grieving family members you patiently answer all their questions. You will probably need to repeat your answers as difficulty with comprehension and concentration are common cognitive grief reactions. They probably are not going to want to engage with you in talking about their loved one but they will eagerly take in all the information you provide to them. They might be the spokesperson for their family members because they are the organizers and the action-oriented folks. They will be the ones to call the funeral home to start making the arrangements. Don’t label or allow these family members to be labeled as “in denial” or “cold.” These grievers use actions to help them process their grief.

Martin and Doka stress that it is important to remember that this is a continuum and rarely is someone exclusively intuitive or instrumental. They believe that most people actually display a more blended grieving style which combines elements of both the intuitive and instrumental grieving styles. Often there is a greater reliance on one style but that is reliant on the person and the situation. So you could also see the outwardly emotional family member also be the one to ask lots of questions. It is rarely an “either-or” situation. You didn’t think it would be that simple, did you?

If I was asked to comment now on the case reviewed by my colleague all those years ago, I would suggest that this father was an intuitive griever and the mother was instrumental griever. I don’t think the gender stereotypes placed on this family by my colleague caused any harm or impacted this family’s donation experience. More so, I hope that this mother and father didn’t inflict these stereotypes on themselves. I hope they didn’t impose any “shoulds” on their grief. I hope they allowed themselves to grieve in a manner that was effective and healthy for them, however that might have looked, and, just as importantly, they allowed their spouse to do the same.

For more information about Instrumental and Intuitive Grief, click here to read an interview with Ken Doka. Also, in 2010, Doka and Martin published an update to their previous book entitled Grieving Beyond Gender: Understanding the Ways Men and Women Mourn, Revised Edition. Additional resources exist at the Hospice Foundation of America (www.hospicefoundation.org) and the Association of Death Education and Counseling (www.adec.org) websites.

Lara Moretti, LSW, CT is the Director of Family Support Services at Gift of Life Donor Program in Philadelphia, PA