Hospital Development

Historically, the language used in family conversations about organ and tissue donation has been thoroughly analyzed. After all, the way this conversation unfolds greatly impacts a family’s willingness to say “yes” to donation. On the other hand, the language used by OPO Hospital Development (HD) staff to lead and inspire our healthcare partners and influence changes in practice has not received the same analysis or attention.

HD Coordinators typically possess excellent written and verbal skills, an ability to cultivate and nurture effective relationships, and a knack for aligning those relationships with hospital systems to implement strategic initiatives that will optimize a hospital’s donation outcomes. All of this takes leadership.

Stephen Covey, best known for the book ‘Seven Habits of Highly Effective People’, suggests a leadership style that fits the work of HD perfectly: Principle-Centered Leadership.

But before we explore this leadership style, let’s take a look at two commonly utilized models, coercive power and utility power.

Coercive and utility power

Coercive power is largely based on fear and intimidation. The changes effected by leadership rely on the use of power and status, and often result in someone doing something out of fear. The follower may be left feeling leveraged and certainly uninspired. The follower “goes along to get along.”

Utility power is based on fairness and equity, and constitutes most working relationships. Leadership relies on fairness in an exchange between two parties, each of whom has something of value to the other. The changes effected in this model are based on someone doing something because it’s worth their while. It’s based on an exchange of support: “I support your issue, you support mine.”

Principle-centered leadership

Principle-centered leadership is about inspiring others to buy in and support a greater purpose and is based on mutual respect and trust. We all know that trust is fragile and takes a long time to develop. Many of us in the OPO community feel time is the enemy, especially for those we serve; transplant candidates on a waiting list. Time is also the enemy of HD Coordinators because the donation process must go right every time, all of the time, and the sooner a HD Coordinator can influence a more optimal process, the more likely it will go well the next time. It’s our job to fix broken or compromised processes and conduct immediate case follow up.

The major benefit of implementing a principle-centered leadership approach is that individuals perceive their leaders as honorable. Trust is established, and there’s a sense of feeling inspired. One’s ability to influence a better process and outcome must be connected to a larger purpose, and done so in an honorable and inspirational way.

When working with hospital partners, we must not only seek their input but, even more important, we must seek to educate ourselves and understand the reasons behind what they’re saying and how they’re feeling. Listening in an empathetic way can be an effective approach to strengthening relationships of trust and discovering more about the perspectives and feelings of our healthcare partners who care for critically ill patients and families. Failing to identify their perspectives or refusing to acknowledge them could have a detrimental and long-term impact on relationships, the process, and outcomes.

What’s your style?

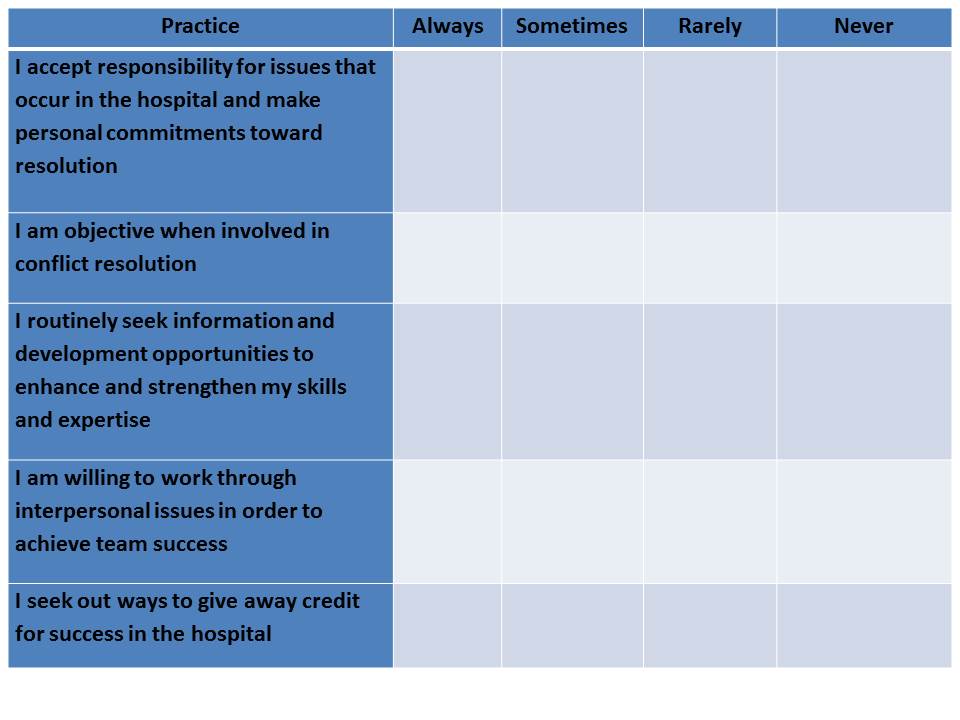

Take a minute and evaluate your own leadership style by considering the following statements:

If you answered “Rarely” or “Never” to any of these statements, maybe it’s time to consider a different approach to leadership. Make a commitment to continually ‘check-in’ on your style or approach, with a goal of improving your relationships, interactions, and outcomes. Partner with your manager, or a trusted member of your OPO, to help you grow and develop in your leadership style. Hold yourself personally accountable to fine-tune your ‘principle-centered leadership’ style.

Gweneth D. O’Shaughnessy is Vice President of Hospital Services at Gift of Life Donor Program in Philadelphia, PA

SBAR (Situation – Background – Assessment – Recommendation), is a model of communication commonly used in healthcare today. SBAR was originally developed by the U.S. Navy as a communication technique that could be used on nuclear submarines. In the late 1990s, Safer Healthcare, an organization that focuses on the delivery of specialized products and services supporting the development and sustainability of high reliability organizations (HRO) within the healthcare industry, helped bring this communication model into the healthcare setting. Since that time, SBAR has been adopted by hospitals and care facilities around the world as a simple yet effective way to standardize communication between care givers.

To bring context to SBAR, users should consider the following framework:

Situation Take 5-10 Seconds to Explain

Background Provide Context and Data

Assessment Describe the Specific Problem/Situation

Recommendation Explain What You Want to Do About it and When

If you’re asking yourself, “Why SBAR?” I offer the following:

- It’s the Joint Commission’s stated industry best practice for standardized communication (primarily spoken) in healthcare for effortlessly structuring critical information;

- It promotes quality, patient safety and high reliability because it helps individuals communicate with each other with a shared set of expectations;

- Staff and physicians use SBAR to share patient information in a clear, complete, concise and structured format, improving communication efficiency and accuracy.

How Does SBAR Translate to Organ Procurement Organization (OPO) Professionals?

It can be used in a “Team Huddle” scenario (spoken by the OPO Transplant Coordinator).

| Situation | “The patient has satisfied death by neurologic criteria and has been pronounced dead by Dr. Smith. The patient is medically suitable to donate organs and tissues.” |

| Background | “This patient was a victim of an MVC. Upon meeting clinical triggers, Sue, the bedside RN, referred this patient as a potential donor. The family has now gathered at the bedside to say their good-byes.” |

| Assessment | “Since it appears that the family understands their loved one has died, we now need to formulate a plan for providing the family with their donation opportunity.” |

| Recommendation | “I suggest that we determine which member of the care team has established a trusting relationship with the family and encourage him or her to introduce me and remain present to support the family during the donation conversation. How does this sound?” |

It can be used in a Physician Meeting (spoken by the OPO Hospital Development Coordinator).

| Situation | “We were called to evaluate one of your patients last week as a potential organ donor. The patient’s heart, lungs, liver and kidneys were all successfully transplanted. I wanted to thank you for all that you did to help make this happen.” |

| Background | “It sounds like the family initially really struggled to understand that their loved one had died. Two of your residents spent an extensive amount of time with them.” |

| Assessment | “After talking with your residents about their experience, I think that they are uncomfortable talking to families about death by neurologic criteria.” |

| Recommendation | “I’d like to provide all of your residents with training on how to explain death by neurologic criteria to families. We can customize it to meet whatever time constraints may exist. What do you think?” |

When the organ donation process goes well, it is usually due to collaboration and communication. Similarly, when it doesn’t go well, it’s largely due to breakdowns in these two areas. In hospitals and critical care areas in particular, optimizing our communication is essential. Getting and keeping members of the care team engaged also requires us to evaluate how we are communicating.

- Can we say more with less?

- Are you receiving non-verbal indicators that the listener is busy, disinterested, or in a rush?

- Are you listening for short answers like “yes” or “no” that are potential signs that you provide “Just the Facts Jack”?

- Is the person that you’re attempting to engage asking questions in return?

- Do they seem curious?

- Do they actually sit down to talk with you?

If they appear to have time for a more lengthy conversation then, by all means, take full advantage of that and enjoy the interaction! If they’re not, SBAR is probably the way to go. I strongly recommend that you incorporate this communication model into your approach just once and see how it works.

For additional SBAR information and resources, please visit:

http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/sbartoolkit.aspx

Gweneth D. O’Shaughnessy is Vice President, Hospital Services at Gift of Life Donor Program in Philadelphia, PA

As with most things related to relationship building, listening is key. When attempting to engage a physician, you’ll need to listen carefully to his or her language and learn to convey your donation information with that language in mind. In other words, speak the physician’s language.

Taking it to the next level, you’ll also need to discern the implications behind the physician’s language. What priorities does the physician’s language convey? It’s a fairly safe bet that those priorities include patient outcomes, family care, and process efficiencies.

It’s also important to consider any barriers to language that may result from your personal communication habits or OPO jargon. Specifically, what do you say and what does your hospital partner hear?

For example, you’ve probably used the term “early referral” when discussing donation. However, the physician could easily hear this as “too early.” Additionally, the physician could begin to use this terminology with colleagues who are less informed about donation. Instead, use the term “timely referral.”

Understand Their Perspective

It’s imperative when engaging physicians to put yourself in their shoes. Consider the following OPO terms and what they mean to us.

- Organ referral

- On-site; early linkage

- Optimize organ function

- Brain death pronouncement

- Collaborative request

- Compliance

Now, consider what each means to the physician. His or her perspective of terms may carry very different, and often sensitive, meanings.

OPO Term What it May Mean to Physician

| Organ referral | Failure and loss |

| On-site; early linkage | Family betrayal |

| Optimize organ function | Caring for a patient with no hope of recovery |

| Brain death pronouncement | Time, resources; futile care |

| Collaborative request | Loss of control |

| Compliance | Dictated practice |

Use your knowledge of the physician’s language and potential perspectives on donation terminology to understand where the physician is coming from. Then use the understanding of those perspectives to align goals or to be on the same page.

Remember, the most likely common ground that exists between you and the physician is the patient. Expand that probable common ground to include the patient’s family and efficiencies and you have a strong foundation for conversation. Donation best practice and policy implementation should center around the benefits of your partnership to this common ground.

Be Transparent

As an OPO professional, it’s your role to serve both the potential donor patient and the potential transplant recipient. This role as dual advocate is an undeniably important one and bears acknowledgement. Transparency in that role is necessary to achieve credibility as a partner and to ensure the best hospital development outcomes. From that foundation—and using language focused on common ground—it’s appropriate to discuss areas that may otherwise be sensitive ones for physicians.

One such area—critical to both maximizing and optimizing donation opportunities—is end-of-life clinical management. How a patient is managed clinically at end-of-life has profound implications on whether—and to what extent—donation is possible. While this area is exhaustive unto itself, it’s a great example of one that can benefit significantly from transparency in your role as dual advocate. The physician may perceive the OPO as “only out to get the organs.” He or she may feel you are asking physicians to perform inappropriate clinical interventions, draw resources away from other patients, or to go against the wishes of a patient or family.

Even though you may feel you are pushing very hard when meeting with a physician, it’s okay that you’re advocating for both potential donors and recipients. These people count on you to do so. But it is also okay that the physician has discomfort or differing opinions. His or her concerns are as real to the physician as your motivation for addressing the topic is to you. Neither should be disregarded.

Examine your use of language, try to speak the physician’s language, and acknowledge your different perspectives. Then use your common ground—usually the patient—to openly discuss your hospital development initiatives with transparency. In the end, this will often equate to full engagement of the physician as a partner.

Elizabeth Spencer has been working in the OPO community since 2002. She was with Washington Regional Transplant Community (WRTC) for nine years, serving as both Director of Hospital Services & Professional Education, and in the clinical division as a Senior Clinical Recovery Coordinator. As Director of Hospital Services & Professional Education, Elizabeth was responsible for oversight of partnerships with area hospitals regarding the implementation of donation best practices, donation educational programs for various hospital staff, hospital data analysis and reporting, hospital donation strategic planning, and hospital policies related to organ and tissue donation.

Many years working on the front lines of family care have enabled me to recognize the importance of the collaborative approach to comprehensive end-of-life care, which, in many cases, includes donation. Because the ultimate goal is a supportive environment when making end-of-life decisions, a shared commitment works best for all stake holders involved in the care of patients and their grieving families.

As a former Manager of Family Services, I’ve heard many OPO colleagues discuss the challenges often encountered during donation cases. Many hospital partners also shared with me the challenges they were presented with during a potential donor case. After comparing the two group’s perceptions, it became evident that there was ample opportunity for stronger and clearer collaboration between both sides, and that the challenges both groups expressed were most often the result of communications breakdowns.

A good starting point for consistent collaboration should be an effective huddle between the OPO and hospital team as soon as the patient meets clinical triggers, repeated as often as needed to assure that all parties are on the same page. The huddle should be comprised of those involved in the care of the patient, including the physician, nurse, chaplain, social worker and members of the palliative care team. Showing discipline to this best practice can provide our hospital partners with a clearer picture of our activities and limit confusion on potential donor cases which leads to optimal care for the family.

By removing the old mindset of working in silos, we can foster stronger relationships that will benefit everyone. We will also create an environment that will allow us to make full use of our hospital partner’s expertise while building trust so they will do the same in return.

Stacey Caruthers has spent the last 20+ years of her professional career helping to advance organ and tissue donation. She was most recently with Indiana Donor Network (formerly Indiana Organ Procurement), serving as both Manager of Family Services and as a Family Services Coordinator.